Integration of New Zealand falcon conservation and vineyard pest

management

The New Zealand falcon (Falco novaeseelandiae) is New Zealand’s only remaining endemic diurnal raptor and is considered a chronically threatened species. Like all New Zealand birds, falcons evolved without the presence of land-dwelling mammalian predators, and therefore lack the morphological and behavioural adaptations necessary to deal with them. Falcons often nest in ‘scrapes’ on the ground, and are prone to high rates of nest mortality from raids by introduced mammalian predators.

Introduced species of passerine birds are a particularly destructive force in the arable farming and vineyard landscapes of New Zealand, and have caused significant economic losses for both growers and associated industries. Vineyards are particularly vulnerable to the destructive patterns of passerine feeding, as grapes represent an abundant and easily targeted food source in summer and autumn. The species that cause the majority of losses to New Zealand vineyards are Blackbirds, Song Thrushes, Starlings and Silvereyes. The total cost of bird damage to the entire New Zealand wine industry may be in excess of $70 million annually, with effects in Marlborough, New Zealand’s largest wine growing region, costing growers millions in combined loss of crop and cost of bird control. As one of only two diurnal raptors in New Zealand, and a specialized avian hunter, the New Zealand falcon is potentially the most effective native predator for controlling pest bird populations. Falcons For Grapes (FFG), is a nonprofit organisation that has relocated falcons from the surrounding hills into the Wairau valley as a means of both providing conservation benefits for falcons, in the form of additional habitat and plentiful prey, and as means of biological control of pest birds. The innovation of FFG is that by relocating falcon chicks to vineyards it aims to create self-sustaining conservation; whereby an increase in falcon numbers, as new habitat and an abundance of prey are made available to them, concomitantly creates a form of integrated pest management that reduces the detrimental effect of passerines in vineyards. Consequently, the FFG initiative has the potential to be strongly beneficial to both falcons and vineyard operators.

Introduced species of passerine birds are a particularly destructive force in the arable farming and vineyard landscapes of New Zealand, and have caused significant economic losses for both growers and associated industries. Vineyards are particularly vulnerable to the destructive patterns of passerine feeding, as grapes represent an abundant and easily targeted food source in summer and autumn. The species that cause the majority of losses to New Zealand vineyards are Blackbirds, Song Thrushes, Starlings and Silvereyes. The total cost of bird damage to the entire New Zealand wine industry may be in excess of $70 million annually, with effects in Marlborough, New Zealand’s largest wine growing region, costing growers millions in combined loss of crop and cost of bird control. As one of only two diurnal raptors in New Zealand, and a specialized avian hunter, the New Zealand falcon is potentially the most effective native predator for controlling pest bird populations. Falcons For Grapes (FFG), is a nonprofit organisation that has relocated falcons from the surrounding hills into the Wairau valley as a means of both providing conservation benefits for falcons, in the form of additional habitat and plentiful prey, and as means of biological control of pest birds. The innovation of FFG is that by relocating falcon chicks to vineyards it aims to create self-sustaining conservation; whereby an increase in falcon numbers, as new habitat and an abundance of prey are made available to them, concomitantly creates a form of integrated pest management that reduces the detrimental effect of passerines in vineyards. Consequently, the FFG initiative has the potential to be strongly beneficial to both falcons and vineyard operators.

|

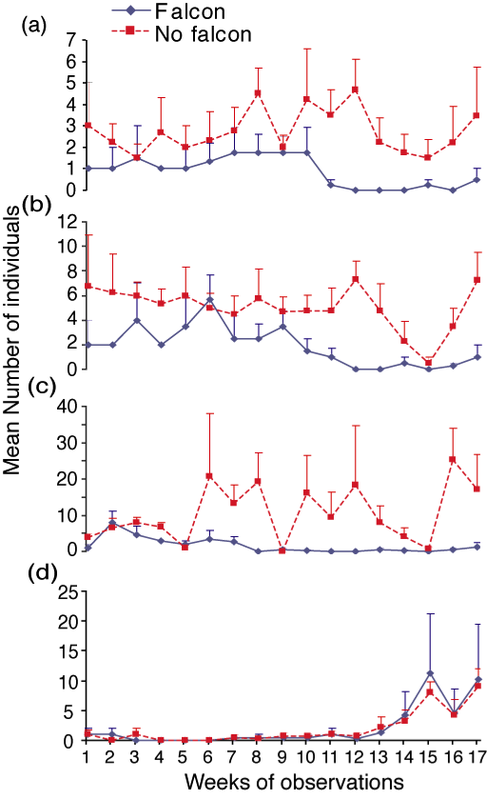

The effects of falcon presence on the abundance of (a) song thrushes (p < 0.01), (b) blackbirds (p = 0.02), (c) starlings (p = 0.06), and (d) silvereyes (p = 0.30, removed from model). Line graphs show the mean (+ S.E.M.) number of individuals observed in each of 17 weeks of veraison at 4 vineyards with resident falcons present (Falcon) and 4 vineyards with falcons absent (No falcon). Grape ripening began at approximately week 12.

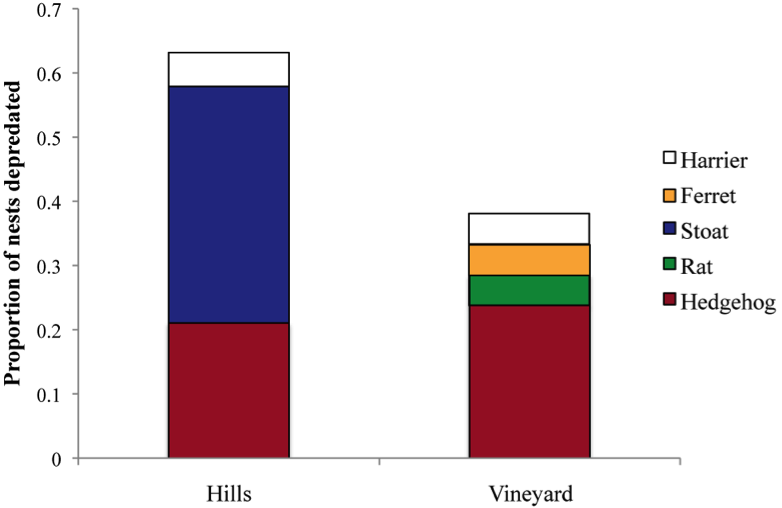

Proportion of artificial New Zealand falcon (Falco novaeseelandiae) nests in unmanaged hill habitat versus managed vineyard habitat predated by hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus), stoats (Mustela erminea), ferrets (Mustela putoris), Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus), and harriers (Circus approximans).

|

Although the success of FFG relied on detailed knowledge of the effect falcon reintroduction is having on the numbers, behaviour and ecology both of falcons and on the passerine species within the vineyards, no rigorous studies had taken place to determine this. Sara’s project addressed how successful FFG is as a method for controlling grape damage caused by passerine birds, as well as its impact on falcon conservation:

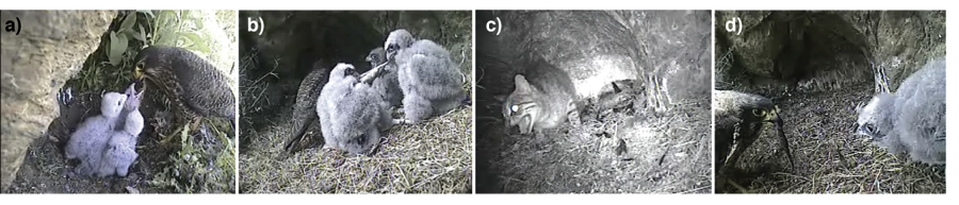

In our ever more populated world, the rapid expansion and intensification of agriculture is driving worldwide biodiversity loss, and the interactions between production landscapes and wildlife conservation are becoming increasingly important. Farming systems depend on ecosystem services such as biological control, while conservationists are calling for the establishment of conservation initiatives in non-preserve landscapes. Despite this, the goals of agriculture and the goals of predator-conservation are rarely mutual. We demonstrate one of the first examples of a mutually beneficial scenario between agriculture and predator conservation, using, as a case study, a reintroduction project that translocated individuals of the threatened New Zealand falcon (Falco novaeseelandiae) from the hills of Marlborough (New Zealand) into vineyards, to determine if predators can survive within an agricultural landscape while simultaneously providing that landscape with biological control services. Examples of vertebrates providing biological control to agriculture are rare. We show that the presence of falcons in vineyards caused an economically important reduction in grape damage worth over US $230/ ha. Falcon presence caused a 78- 83% reduction in the number of introduced European pest birds, which resulted in a 95% reduction in the damage caused by these species. Falcon presence did not cause a reduction in the abundance of the native silvereye (Zosterops lateralis), but did halve the damage caused by this species. To assess the conservation value of the falcon translocations, We used remote videography, direct observations and prey analysis to measure the behavioural changes associated with the relocation of falcons from their natural habitat in the hills and into vineyards. Falcons in vineyard nests had higher nest attendance, higher brooding rates, and higher feeding rates than falcons in hill nests. Additionally, parents in vineyard nests fed their chicks a greater amount of total prey and larger prey items compared to parents in hill nests. We also found an absence of any significant diet differences between falcons in hill and vineyard habitats, suggesting that the latter may be a suitable alternative habitat for falcons. Because reintroduced juvenile falcons were released in areas devoid of adult falcons, it was possible that they were missing essential training normally provided by their parents. We used direct observations to demonstrate that the presence of siblings had similar effects to the presence of parents on the development of juvenile behaviour, with individuals flying, hunting, and playing more often when conspecifics were present. Finally, through the use of artificial nests and remote videography, we identified that falcons nesting in vineyards are likely to suffer lower predation rates. We also found that falcons in vineyards are predated by a less dangerous suite of animals (such as hedgehogs, Erinaceus europaeus, and avian predators), than their counterparts in the hills, which are predated by more voracious species (such as stoats, Mustela erminea, and feral cats, Felis catus). Although agricultural regions globally are rarely associated with raptor conservation, and the ability of raptors to control the pests of agricultural crops has not been previously quantified, these results suggest that translocating New Zealand falcons into vineyards has potential for both the conservation of this species, and for providing biological control services to agriculture. This project was funded by the Brian-Mason Technical Trust and was carried out by PhD student Sara Kross. Relevant publications |